790. Domino and Tromino Tiling

Description

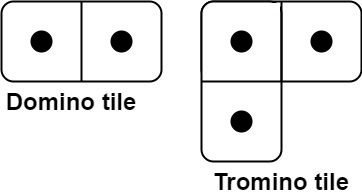

You have two types of tiles: a 2 x 1 domino shape and a tromino shape. You may rotate these shapes.

Given an integer n, return the number of ways to tile an 2 x n board. Since the answer may be very large, return it modulo 109 + 7.

In a tiling, every square must be covered by a tile. Two tilings are different if and only if there are two 4-directionally adjacent cells on the board such that exactly one of the tilings has both squares occupied by a tile.

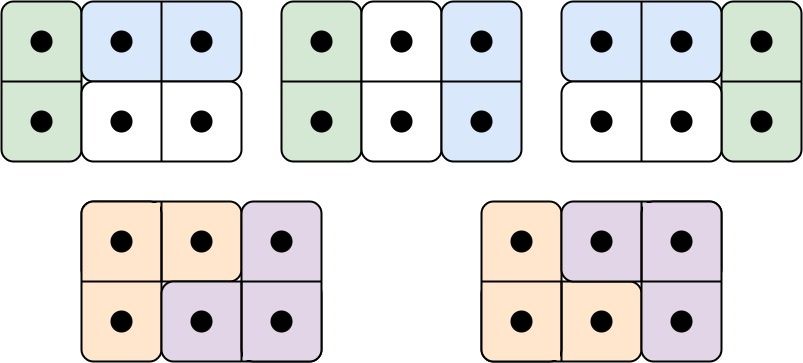

Example 1:

Input: n = 3 Output: 5 Explanation: The five different ways are shown above.

Example 2:

Input: n = 1 Output: 1

Constraints:

1 <= n <= 1000

Solutions

Solution 1: Dynamic Programming

First, we need to understand the problem. The problem is essentially asking us to find the number of ways to tile a $2 \times n$ board, where each square on the board can only be covered by one tile.

There are two types of tiles: 2 x 1 and L shapes, and both types of tiles can be rotated. We denote the rotated tiles as 1 x 2 and L' shapes.

We define $f[i][j]$ to represent the number of ways to tile the first $2 \times i$ board, where $j$ represents the state of the last column. The last column has 4 states:

The last column is fully covered, denoted as $0$

The last column has only the top square covered, denoted as $1$

The last column has only the bottom square covered, denoted as $2$

The last column is not covered, denoted as $3$

The answer is $f[n][0]$. Initially, $f[0][0] = 1$ and the rest $f[0][j] = 0$.

We consider tiling up to the $i$-th column and look at the state transition equations:

When $j = 0$, the last column is fully covered. It can be transitioned from the previous column's states $0, 1, 2, 3$ by placing the corresponding tiles, i.e., $f[i-1][0]$ with a 1 x 2 tile, $f[i-1][1]$ with an L' tile, $f[i-1][2]$ with an L' tile, or $f[i-1][3]$ with two 2 x 1 tiles. Therefore, $f[i][0] = \sum_{j=0}^3 f[i-1][j]$.

When $j = 1$, the last column has only the top square covered. It can be transitioned from the previous column's states $2, 3$ by placing a 2 x 1 tile or an L tile. Therefore, $f[i][1] = f[i-1][2] + f[i-1][3]$.

When $j = 2$, the last column has only the bottom square covered. It can be transitioned from the previous column's states $1, 3$ by placing a 2 x 1 tile or an L' tile. Therefore, $f[i][2] = f[i-1][1] + f[i-1][3]$.

When $j = 3$, the last column is not covered. It can be transitioned from the previous column's state $0$. Therefore, $f[i][3] = f[i-1][0]$.

We can see that the state transition equations only involve the previous column's states, so we can use a rolling array to optimize the space complexity.

Note that the values of the states can be very large, so we need to take modulo $10^9 + 7$.

The time complexity is $O(n)$, and the space complexity is $O(1)$. Where $n$ is the number of columns of the board.

Python3

class Solution:

def numTilings(self, n: int) -> int:

f = [1, 0, 0, 0]

mod = 10**9 + 7

for i in range(1, n + 1):

g = [0] * 4

g[0] = (f[0] + f[1] + f[2] + f[3]) % mod

g[1] = (f[2] + f[3]) % mod

g[2] = (f[1] + f[3]) % mod

g[3] = f[0]

f = g

return f[0]

Java

class Solution {

public int numTilings(int n) {

long[] f = {1, 0, 0, 0};

int mod = (int) 1e9 + 7;

for (int i = 1; i <= n; ++i) {

long[] g = new long[4];

g[0] = (f[0] + f[1] + f[2] + f[3]) % mod;

g[1] = (f[2] + f[3]) % mod;

g[2] = (f[1] + f[3]) % mod;

g[3] = f[0];

f = g;

}

return (int) f[0];

}

}

C++

class Solution {

public:

int numTilings(int n) {

const int mod = 1e9 + 7;

long long f[4] = {1, 0, 0, 0};

for (int i = 1; i <= n; ++i) {

long long g[4];

g[0] = (f[0] + f[1] + f[2] + f[3]) % mod;

g[1] = (f[2] + f[3]) % mod;

g[2] = (f[1] + f[3]) % mod;

g[3] = f[0];

memcpy(f, g, sizeof(g));

}

return f[0];

}

};

Go

func numTilings(n int) int {

f := [4]int{}

f[0] = 1

const mod int = 1e9 + 7

for i := 1; i <= n; i++ {

g := [4]int{}

g[0] = (f[0] + f[1] + f[2] + f[3]) % mod

g[1] = (f[2] + f[3]) % mod

g[2] = (f[1] + f[3]) % mod

g[3] = f[0]

f = g

}

return f[0]

}

TypeScript

function numTilings(n: number): number {

const mod = 1_000_000_007;

let f: number[] = [1, 0, 0, 0];

for (let i = 1; i <= n; ++i) {

const g: number[] = Array(4);

g[0] = (f[0] + f[1] + f[2] + f[3]) % mod;

g[1] = (f[2] + f[3]) % mod;

g[2] = (f[1] + f[3]) % mod;

g[3] = f[0] % mod;

f = g;

}

return f[0];

}

Rust

impl Solution {

pub fn num_tilings(n: i32) -> i32 {

const MOD: i64 = 1_000_000_007;

let mut f: [i64; 4] = [1, 0, 0, 0];

for _ in 1..=n {

let mut g = [0i64; 4];

g[0] = (f[0] + f[1] + f[2] + f[3]) % MOD;

g[1] = (f[2] + f[3]) % MOD;

g[2] = (f[1] + f[3]) % MOD;

g[3] = f[0] % MOD;

f = g;

}

f[0] as i32

}

}